http://haplogroupi2b1ismine.wordpress.com/the-germani-germanic-peoples-origins-and-history/

The Germani

Who were they?

The Germani entered Roman consciousness as unknown enemies, suddenly looming from the misty distance. Not that the Romans had a collective ethnic name for the tribes who swooped upon them in 113 BC, driven by the flooding of their own lands to look for a new homeland. Only as the frontiers of the Roman Empire expanded up to the North Sea in the next century were the Cimbri securely located by Roman geographers in Jutland and the Teutones within Germania. 1Plutarch, The Lives, The Life of Marius, 11; Lucius Annaeus Florus, The Epitome of Roman History, book 1, chapter 38; Strabo, Geography, book 7, chapter 2, sections 1-2; Claudius Ptolemy, The Geography, book 2, chapter 10; Res Gestae Divi Augusti, chapter 26; Tacitus, Germania, 37; Pliny, Natural History, book 4, chapter 28.

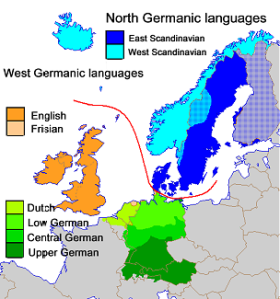

The Germani were not a unified people. But they did have a language in common. Linguists have reconstructed that language – Proto-Germanic, the parent of a family of languages which includes Danish, Dutch, English, German, Norwegian and Swedish. Modern linguists named the branch after the most common Roman name for these peoples – the Germani, first mentioned by Julius Caesar.2Julius Caesar, Gallic War, book 4; An alternative Roman name was Alamanni. When Tacitus (56–117AD) enquired of Germani the origin of their name, he was informed that it just happened to be the name of the tribe who first crossed the Rhine and pushed into Gaul. While the tribe had since renamed themselves the Tungri, the terror-inducing name

Germanhad stuck in the minds of their enemies, and been recently adopted by the Germani themselves as the collective name for all their tribes.3Tacitus, Germania, chapter 2. The geographer Ptolemy described Germania as bordered by the Rhine, the Vistula and the Danube Rivers, but in Greater Germania he included Jutland (as the Cimbrian peninsula). Also included was the Scandinavian peninsula, described as a very large island called Scandia.4Ptolemy, The Geography, book 2, chapter 10. The ancient Greeks and Romans did not penetrate deep enough into the Gulf of Bothnia to realise that Scandia was actually linked to Finland.

Germanic genetic markers

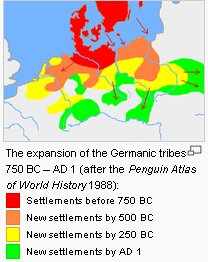

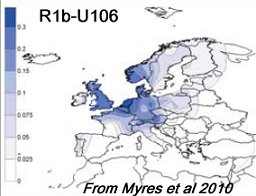

As we shall see, the Germani apparently sprang from a mixture of peoples. So it is no surprise that they did not have just one genetic marker, to judge by their descendants. If and when scientists find ancient Y-DNA from men that we can guess spoke Proto-Germanic, it is most likely to be a mixture of I1, R1a1a, R1b-P312 and R1b-U106, to name only the most common haplogroups. I1 may have arrived with hunter-gatherers. As mentioned in the Indo-European genetics section, R1a1a is shared by Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Iranian and Indic speakers. The recent discovery of SNPs which define subclades of R1a1a offer promise of being able to distinguish a Nordic type.

R1b-P312 peaks in western Europe and correlates best with the former Celtic and Italic speaking zone. Its subclade R1b-L21 is strongly concentrated in the more northerly former Celtic-speaking region. So the presence of R1b-P312* and R1b-L21 in present-day Germanic-speakers no doubt largely reflects the fact that Germani spread out over parts of the former Celtic area, such as the Alps, the Netherlands and lowland Britain, absorbing existing populations as they went. There has also been migration from former Celtic areas into Scandinavia over the centuries, for example Scottish communities in 16th and 7th-century Bergen and Gothenburg.5S. Murdoch and A. Grosjean (eds.), Scottish Communities Abroad in the Early Modern Period (Leiden, 2005). Some of the L21 in Norway falls into subclades rarely seen outside the British Isles and can be presumed to have arrived from there.6See G.B. J. Busby et al, The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269,Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Published online before print, August 24, 2011 for the distribution of L21/S145 and its subclade M222. Yet most of the L21 in Scandinavia does not. So it seems a reasonable supposition that some R1b-P312* and L21 arrived in Scandinavia with Bell Beaker folk, or in Bronze Age trade. We should not imagine an impassible genetic divide between overlapping and interacting cultures. Some subclades of R1b-P312 have a distinctly Nordic distribution. Those defined by L165/S68 and L238/S182 are found in Scandinavia and the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland, which suggests that they are Norse markers which arrived in the Isles with Vikings.7A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A genetic journey (2011), pp. 181-3.

R1b-U106 has its peak in northern Europe and a distribution which correlates fairly well with Germanic speakers, past and present. A sprinkling of men within that distribution carry the parent clade R1b-L11*, opening up the possibility that R1b-U106 arose from R1b-L11* in Northern Europe. However its density of distribution there suggests that it arose at the head of a wave of advance into Northern Europe. Of its known subclades only U198 was included in the study by Natalie Myres and colleagues. On the basis of the samples collected, U198 is found in The Netherlands, Germany, Russia, Denmark and Northern England (which was settled by Angles from what is now Denmark).8N.M Myres et al., A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe, European Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 19 (2011), pp. 95–101; Fulvio Cruciani et al., Strong intra- and inter-continental differentiation revealed by Y chromosome SNPs M269, U106 and U152, Forensic Science International: Genetics, vol. 5, no. 3 (June 2011), e49-52.. Drawing on more detailed data for Britain, James Wilson reports that U198 is a strongly Anglian marker, concentrated in the East of England, but also found in South-East Scotland, where Angles also settled.9A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A Genetic Journey (2011), pp. 145-146. However preliminary results from the Old Norway Project show that U198 is found in Norway and Sweden as well as Denmark,10S. Harding, Viking DNA: paper read at the Gothenburg Museum Conference, October 14th 2011. so some caution is needed in its interpretation. It could have reached Russia with Rus from Sweden, or much later German immigrants.

Nor should we expect all Germanic speakers to look alike. Tacitus claimed that the Germani were all tall, blue-eyed and red-haired.11Tacitus, Germania, chapter 4. Strabo described them as taller than the Celts and with yellower hair.12Strabo, Geography, book 7, chapter 1. The Byzantines called them

The Light-Haired Peoples,13Maurice’s Strategikon: handbook of Byzantine military strategy, trans. G.T. Dennis (1984), p. 119:

The Light-Haired Peoples, such as the Franks, Lombards and others like them.or tall, fair and handsome.14Procopius, The History of the Wars, book 3, section 2, referring to the Goths, Vandals, Visigoths and Gepids. All such generalisations are suspect. They were not based on a scientific survey. But it is reasonable to suppose that there was a higher incidence of fair hair and blue eyes among the Germani than among southern Europeans, just as there is today among the Scandinavians.

Podiatrist Phyllis Jackson noticed a difference between the typical foot-shape of the English (broad, with the toes sloping down sharply) and that prevailing in Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland and Wales (narrow with a more level toe line). She went on to investigate skeletal material and found a considerable difference between the feet of the Roman-British and those buried with Anglo-Saxon grave goods.15P. Jackson, Footloose in archaeology, Current Archaeology, no. 144 (1995), pp. 466-70, and Journal of British Podiatric Medicine, vol. 51, no. 5 (1996), pp. 67-70. Given the lack of further research, it is impossible to say if these differences relate only to the British Isles, or reflect a common foot-type among the Germani.

Proto-Germanic

Linguists calculate that Proto-Germanic was spoken around 500 BC.16Donald A. Ringe, A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006), p.67. A language develops within a communicating group. In the days before modern transport and the nation state, a communicating group could not cover a vast territory. The area in which Proto-Germanic evolved was far smaller than the spread of its daughter languages today. We would expect a linguistic boundary to also be a cultural boundary. So the finger points at the Nordic Bronze Age (1730-500 BC) as the cradle of Proto-Germanic. It was a comfortable cradle for many a year. The Nordic Bronze Age began in a welcoming warmth. An earlier climate shift made Southern Scandinavia as warm as present-day central Germany. Groups of people from the widespread Corded Ware and Bell Beaker Cultures had moved north into Jutland and the coasts of what are now Norway and Sweden. There they melded with descendants of the Funnel Beaker and Ertebølle people into a rich Bronze Age culture.17H. Vandkilde, A review of the Early Late Neolithic period in Denmark: practice, identity and connectivity online in http://www.jungsteinsite.de 15 December 2005; K. Kristiansen, Proto-Indo-European languages and institutions: an archaeological approach, in M. Van der Linden and C. Jones-Bley (eds.), Departure from the Homeland: Indo-Europeans and Archaeology (2009), pp. 111-140. The wealth and technical excellence of its bronze objects is impressive. Trade was important to this society. So was seacraft. Voyages linked Jutland and Scandia in one communicating web.18B. Cunliffe, Europe Between the Oceans (2008), pp. 213-221.

However the climate gradually deteriorated, bringing increasingly wetter and colder times to Jutland, culminating in so steep a decline in the decades around 700 BC that much agricultural land was abandoned and bog built up.19K.E. Barber et al, Late Holocene climatic history of northern Germany and Denmark: peat macrofossil investigations at Dosenmoor, Schleswig-Holstein, and Svanemose, Jutland, Boreas, vol. 33, no. 2 (2004), pp. 132-144. Pollen history reveals a similar picture in Southern Sweden. Around 500 BC forest encroached on areas that had long been farmland.20G.E. Hannon et al., The Bronze Age landscape of the Bjäre peninsula, southern Sweden, and its relationship to burial mounds, Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 35, no. 3 (March 2008), pp. 623-632. Meanwhile an influence from eastern Sweden reached the southern Baltic shores in the Late Bronze Age, providing a clue to where some of the Scandinavian farmers were going.21A. Kaliff, Gothic Connections: Contacts between eastern Scandinavia and the southern Baltic coast 1000 BC – 500 AD, Occasional Papers in Archaeology 26, (Uppsala 2001).

Scandinavia was not utterly deserted in this period. Hunters and fishermen could survive where farming failed.The Saami even expanded. The original homeland of Proto-Saami is deduced to be southern Finland. Around 650 BC Kjelmøy ceramics spread west into Scandinavia, probably marking the arrival of the Saami-speakers.22A. Aikio, On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory, Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuren Aikakauskirja/Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne, vol. 91 (2006), pp. 9-55. Between 400 AD and 1300 AD they lived over a larger area of Sweden than they do now.23Noel D. Broadbent, The search for a past: the prehistory of the indigenous Saami in northern coastal Sweden, in Vesa-Pekka Herva (ed.), People, Material Culture and Environment in the North: Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Archaeological Conference, University of Oulu, 18-23 August 2004 (2006), pp. 13-25. Perhaps the Saami melded with hardy, hunting descendants of the Ertebølle who had never relinquished that way of life. That might explain why the Y-DNA haplogroup I1 is the second most common among the Saami.24K. Tambets et al., The western and eastern roots of the Saami: The story of genetic outliers told by mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 74, no. 4 (2004), pp. 661-682.

Farming continued on some dry ridges, but it seems that many farmers shifted southward.25S. Perdikaris, Pre-Roman Iron Age Scandinavia, in P.Bogucki and P.J. Crabtree (eds.), Ancient Europe 8000 BC–AD 1000:Encyclopaedia of the Barbarian World, Vol. I The Mesolithic to Copper Age (c.8000-2000 B.C.) (2004). If Germanic-speakers began spilling south out of Jutland, they would soon encounter the iron-working Celts expanding northwards. The Jastorf Culture seems to be the result. This was an Iron Age culture in what is now north Germany c. 600-0 BC. Though clearly evolving out of the Nordic Bronze Age, elements of the (Celtic) Halstatt Culture are detectable. This was probably the time in which Proto-Germanic borrowed the Celtic words for

ironand

king.26J.P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997), pp. 321-2.

So Proto-Germanic in the end was crafted out of crisis. It seems that its final development was in the compact region of the Jastorf Culture. But by the time Tactitus wrote, Germania was far larger. The border between the Roman Empire and Germania was the river Rhine.27Tacitus, Germania, chap.1. An expanding language tends to split into dialects, as the spread becomes too wide for constant communication. Eventually these dialects develop into separate languages.

Branches of the Germanic tree

The first language to split away was East Germanic.28D.A. Ringe, A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006), p. 213. The Goths, Gepids, Vandals and Burgundians all seem to have spoken forms of East Germanic, though the only written record is of Gothic. Spreading gradually southward from the Baltic to the Black Sea or the Hungarian Plain, they bore the brunt of the attack as the Huns swept into Europe along the steppe. Most were pushed westward into Roman territory. Some of the scattered tribes wandered as far as Spain and North Africa in the search for new homelands. See the Goths and Vandals for more.

From 200 BC to 200 AD a warm, dry climate favoured cereal cultivation once more in Scandinavia.29S. Perdikaris, Pre-Roman Iron Age Scandinavia, in P. Bogucki and P.J. Crabtree (eds.), Ancient Europe 8000 BC–AD 1000: Encyclopaedia of the Barbarian World, Vol. I The Mesolithic to Copper Age (c. 8000-2000 B.C.) (2004). As farmers were enticed northward, the dialect that developed into Old Norse broke away from the core. Various attempts to date the split by glottochronology have yielded dates between 70 and 200 AD. It was recorded in runes from c. 300 AD onwards. By around 1000 AD Old Norse was dividing into eastern and western dialects that later evolved into the modern Scandinavian languages.30V. Blažek, On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey, Linguistica online(November 2005); J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams (eds.), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997), p. 22; O.W. Robinson, Old English and its closest relatives: a survey of the earliest Germanic languages (1994), p. 16 gives an earlier date (c. 150 AD) for the earliest runes.

During the Medieval Warm Period (c. 900-1200) Scandinavians thrived and spread by sea in a series of adventures, colonising Iceland and Greenland and even setting foot in North America.31B.Fagan, The Little Ice Age: How climate made history 1300-1850 (2000), chapter 1. Their raids into Europe gave them the feared name of Vikings. Yet they settled too, taking Old Norse to Iceland, Shetland and Orkney.

Western Germanic evolved from the rump of Proto-Germanic, and began to split into separate strands with the migrations westward. The earliest split came around 400 AD as groups of Angles, Saxons and Jutes left for England, where Old English developed. German, Dutch and Frisian are among the other living languages on this branch.

Upper German is spoken in southern Germany, Austria and large parts of Switzerland; this whole region was once Celtic-speaking. Thus some of the most famous Celtic Iron-Age sites, including Hallstatt and La Tène, are now within the Upper German-speaking zone.

Franks and Anglo-Saxons

The Franks were the Germanic people who gave France its name, while its language remained Romance, inherited from the Roman Empire. This makes an interesting contrast to England, which takes both its name (Angle-land) its language (Angle-ish) from its Germanic invaders. Why are these patterns so different?

The Franks conquered most of Roman Gaul without drastically disrupting its social structure. They inserted themselves as a new ruling class into the vacuum left by the collapse of Roman rule. They made use of the apparatus of Roman government. Christianity, established in the Late Roman period, continued to flourish unchecked. South of the Loire, descendants of the old Roman elites continued to run the estates acquired by their ancestors, in contrast to the collapse of the villa economy in England. Whereas in England urban life decayed, the Roman towns of Gaul retained at least a half-life under the Franks as the centres of bishoprics or secular government. This continuity helps to explain both the greater preservation of Roman monuments in France, and the preservation of the Romance language. By contrast the Anglo-Saxons created their own social structure. Their first settlements were scattered farmsteads. There is little sign of hierarchy until the 7th century, and then only a distinction between royal sites and others. Not that there was a sole ruler of England until centuries later. These early kings were local tribal leaders, just as likely to fight each other as to fight the Britons.32A. Woolf, Apartheid and Economics in Anglo-Saxon England, chapter 10 in N. Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (2007); P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), chap. 6: Franks and Anglo-Saxons.

The Frankish approach is similar to that of the Goths, who entered the Roman Empire in its time of strength. The Goths were familiar with the Roman system of government long before the opportunity came to take over part of the crumbling empire. They became Romanised. To what degree is this true of the Franks? The Franks do not appear in the record under that name until the late Roman period. Several tribes close to the Roman frontier were considered Franks by the Romans: the Ampsivarii, Bructerii, Chattuarii, Chamavi and Salii.33P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), p. 306. The Salii were bold enough to cross the border and settle at Toxiandria (a region between the Meuse and the Scheldt rivers in the present-day Netherlands and Belgium). Emperor Julian regularised the position by taking their surrender in 358 AD.34Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History, 17. 8.3. As with the Goths, some Franks served in the Roman army. A few rose to top commands.35P. Heather,Empires and Barbarians (2009), p. 306.

By contrast the Germani entering Britain had no use for Roman ways. They initially ignored Roman towns and villas. They created new settlements with Germanic names.36The distribution of certain Germanic place-names suggests that some of the movement into Britain came from Saxony via the Low Countries and the Pas de Calais, with settlers opting to cross to Britain rather than press further westward into Neustria. See J. Udolph, Namenkundliche Studien zum Germanenproblem, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Ergänzungsbände 9 (1994); S. Hilsberg, Place-Names and Settlement History: Aspects of Selected Topographical Elements on the Continent and in England, MA thesis, Leipzig 2009: online http://place-names.co.uk/Roman building methods ceased; those had been based on an imperial economy, generating a huge surplus income that could be poured into specialist labour. By contrast the homeland of the Anglo-Saxons was on the fringes of farming, where agricultural surplus was low. They were accustomed to building in timber.

From the Bronze Age to the 7th century AD, the timber longhouse was the standard dwelling from southern Scandinavia to what is now northern Germany. The model shown right of a Bronze-Age settlement at Flögeln, Lower Saxony, includes a typical longhouse, which sheltered both cattle and people in separate sections. Houses at Flögeln gradually increased in average length from the first to the 5th centuries AD. It is a similar picture in Denmark. Germanic farmers were flourishing in an improving climate it seems. Yet between the 5th and 6th centuries there was a sudden reverse trend, with long-houses becoming shorter, and cattle being moved to a separate byre. This was just the time of the migrations. That partly explains why the traditional long-house did not arrive in Britain with the Saxons, though other types of Germanic building did. A more pressing reason would be simple lack of labour. Pioneers in a new land might find themselves short-handed.37H. Hamerow, Early Medieval Settlements: The archaeology of rural communities in North-West Europe 400-900 (2002), chapter 2. An early Anglo-Saxon village occupied 420-650 AD has been reconstructed at West Stow, Suffolk (below).

The Anglo-Saxon pattern suggests that migrants were bringing their families with them, and settling down to farm the land. Indeed an isotope study of the Anglian cemetery at West Heslerton, North Yorkshire, shows that both men and women were among the early settlers there.38J. Montgomery et al., Continuity or Colonization in Anglo-Saxon England? Isotope Evidence for Mobility, Subsistence Practice, and Status at West Heslerton, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 126 (2005), pp. 123–138. The very earliest arrivals in England may have been mercenaries invited by British leaders, as the 6th-century British author Gildas tells us, but by his day the weakness of post-Roman Britain had attracted a major thrust of Germani into eastern England. He wails that those Britons who were not slain or enslaved were pushed westwards into the mountains, or even overseas.39Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, chapters 23-25. (The influx of Britons into Armorica changed its name to Brittany.) Bede famously said in the 8th century that so many Angles had moved to Britain that Angeln remained deserted even to his own day.40Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, I.15. He was reporting hearsay, but archaeological evidence does indicate a post-Roman fall in population in North-West Germany, along the Frisian coast and particularly in Schleswig-Holstein, the heartland of the Angles. People along the coast were flooded out by rising sea levels, but even inland the number of settlements decreased drastically.41H. Hamerow, Early Medieval Settlements (2002), pp. 108-10. So mass migration is indicated.

Even so we should not exaggerate the differences between the early Frankish domain and early Anglo-Saxon England. The Roman habit of erecting monumental stone buildings could not be sustained anywhere in the West in the new economic climate. It was not until Charlemagne forged an empire that the Franks could revive Roman building methods in the style known as Romanesque. By the end of the reign of Charlemagne in 814, other German-speaking regions had been added to that German-speaking core in Austrasia. As the Franks spread across Gaul, other Germanic tribes had spread south as far as present-day Austria and Switzerland. The Franks were initially content to be acknowledged as overlords of these regions, but Charlemagne drew them into the Frankish Empire, along with Saxony. Thus he united more of Europe than anyone had done since the fall of the Roman Empire. The Franks had welded together a Romance-speaking west to a German-speaking east, but it was not to last. The Eastern Frankish kingdom broke away in 911. Within present-day France, only Alsace is traditionally German-speaking.

Regional variation in France and England

The stark contrast between the modus operandi of the Anglo-Saxons and the Franks masks regional variation in both cases. The first areas to be taken over bear the hallmarks of a folk movement. Some later territorial acquisitions were governed more than settled. Across what is now northern France (c. 500 AD) and East Anglia, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire (c. 450 AD) we see the sudden appearance of a new type of burial. In these areas there are Germanic place-names. Such names extended over most of England by the time of the Domesdaysurvey in 1068, though the degree of Anglo-Saxon settlement diminished towards the west, and Cornwall retained a Celtic language. The Anglo-Saxons had taken their conquest of England in stages. Their advance halted for a generation after the Battle of Badon, as Gildas tells us. In his day much of the west and north of the former Roman province remained British. That gave the Anglo-Saxons time to gain reinforcements from a continuing influx of Germanic settlers, as well as their own expanding population. When they pressed westwards once more in the 550s, they may have been taking advance of a British population depleted by plague.

In France we can credit the different state of affairs to Clovis, King of the Franks (c. 482-511 AD). This mighty leader was so successful in battle that he gained far more land than his people could settle. South of the Loire a late Roman society continued to flourish. In Northern France there was more social disruption. Yet it was the region of Gaul first won from the Romans by the Franks, decades before Clovis, that became German-speaking: or at least a large part of that territory between the Rhine and the Somme.42A. Woolf, Apartheid and Economics in Anglo-Saxon England, chapter 10 in N. Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (2007); P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians(2009), chap. 6: Franks and Anglo-Saxons, maps 11-12.

Both France and Britain gained another influx of Germanic blood from the Vikings, which complicates the genetic picture. Thus far genetic studies have been able to identify the input of Norwegian Vikings to Orkney and Shetland. It is more difficult to distinguish between Anglo-Saxons and Danish Vikings, since both came from Jutland. York was a Viking town, so it is no surprise to see the marked similarity of Y-DNA in York and Denmark. Yet the genetic impact of the Anglo-Saxons in England cannot be denied. Even today, after centuries of moving and mixing, that impact remains highest in East Anglia.43M.E. Weale, Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 19 (2002), pp. 1008-1021; C. Capelli et al., A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles, Current Biology, vol. 13 (May 27, 2003), pp. 979–984; S. Goodacre et al., Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods, Heredity, vol. 95 (2005), pp. 129–135. Preliminary analysis of the large People of the British Isles study

suggest a very substantial contribution to the central population from the East, putatively the Anglo-Saxons. Intriguingly, the difference between the autosomal and NRY analysis suggests that the male Eastern contribution may be less than the female.44B. Winney et al., People of the British Isles: preliminary analysis of genotypes and surnames in a UK-control population, European Journal of Human Geneticsadvance online publication, 10 August 2011.

Ramos-Luis and colleagues found little difference in the Y-DNA signatures of a selection of regions of France, with two exceptions: Brittany and Alsace. Subclades of haplogroup R1b dominate all the tested regions, as with the rest of Western Europe. R1b-M269 is the most common, except in formerly German-speaking Alsace, where R1b-U152 is just a shade ahead in the sample. As we might expect, Alsace also beat other French regions in its level of U106, which tends to cluster within Germanic-language countries. Brittany on the other hand has a level of R1b-M269 twice as high as the other regions, but also has a higher level of haplogroup I1 (12%) than any of the other regions tested, which run from 3% to 8%.45E. Ramos-Luis et al., Phylogeography of French male lineages, Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series, vol. 2 (2009), pp. 439–441; unpublished data from this study supplied by its authors. Brittany was only briefly subjugated by the Franks and provided a refuge for Britons fleeing the Anglo-Saxon advance. However Brittany was conquered by Vikings in 919. The level of haplogroup I1 found in Lower Normandy (11.9%) is effectively the same as that in Brittany.46S. Rootsi et al., Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 75 (2004), pp.128-137. Thus I1 would appear to be a Viking rather than Frankish signature in Brittany. In Britain the Western Isles, where Vikings settled, has almost as much I1 (18%) as Germany and Denmark (19%), though Norfolk – settled by Angles – is not far behind at 17%.47C. Capelli et al., A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles,Current Biology, vol. 13 (May 27, 2003), pp. 979–984.

Just as R1b-U152 and R1b-U106 cluster together in Alsace, so they do in eastern Scotland and East Anglia. This may reflect succeeding waves of incomers from the Continent, all preferring the best arable land, the earliest in the Iron Age, but the later ones of Angle and Norse. The L2 subclade of U152 may prove helpful in distinguishing the Germanic migrants from earlier ones.48A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A Genetic Journey (2011).

Notes

If you are using a browser with up-to-date support for W3C standards e.g. Firefox, Google Chrome, IE 8 or Opera, hover over the superscript numbers to see footnotes online. If you are using another browser, select the note, then right-click, then on the menu click View Selection Source. If you print the article out, or look at print preview online, the footnotes will appear here.

- Plutarch, The Lives, The Life of Marius, 11; Lucius Annaeus Florus, The Epitome of Roman History, book 1, chapter 38; Strabo, Geography, book 7, chapter 2, sections 1-2; Claudius Ptolemy, The Geography, book 2, chapter 10; Res Gestae Divi Augusti, chapter 26; Tacitus, Germania, 37; Pliny, Natural History, book 4, chapter 28;

- Julius Caesar, Gallic War, book 4; An alternative Roman name was Almanni.

- Tacitus, Germania, chapter 2.

- Ptolemy, The Geography, book 2, chapter 10.

- S. Murdoch and A. Grosjean (eds.), Scottish Communities Abroad in the Early Modern Period (Leiden, 2005).

- See G.B. J. Busby et al, The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Published online before print, August 24, 2011 for the distribution of L21/S145 and its subclade M222.

- A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A genetic journey (2011), pp. 181-3.

- N.M Myres et al., A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe, European Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 19 (2011), pp. 95–101; Fulvio Cruciani et al., Strong intra-and inter-continental differentiation revealed by Y chromosome SNPs M269, U106 and U152,Forensic Science International: Genetics, vol. 5, no. 3 (June 2011), e49-52.

- A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A Genetic Journey (2011), pp. 145-146.

- S. Harding, Viking DNA: paper read at the Gothenburg Museum Conference, October 14th 2011.

- Tacitus, Germania, chapter 4.

- Strabo, Geography, book 7, chapter 1.

- Maurice’s Strategikon: handbook of Byzantine military strategy, trans. G.T. Dennis (1984), p. 119:

The Light-Haired Peoples, such as the Franks, Lombards and others like them.

- Procopius, The History of the Wars, book 3, section 2, referring to the Goths, Vandals, Visigoths and Gepids.

- P. Jackson, Footloose in archaeology, Current Archaeology, no. 144 (1995), pp.466-70, and Journal of British Podiatric Medicine, vol. 51, no. 5 (1996), pp. 67-70.

- D. A. Ringe, A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006), p.67.

- H. Vandkilde, A review of the Early Late Neolithic period in Denmark: practice, identity and connectivity online in http://www.jungsteinsite.de 15 December 2005; K. Kristiansen, Proto-Indo-European languages and institutions: an archaeological approach, in M. Van der Linden and C. Jones-Bley (eds.), Departure from the Homeland: Indo-Europeans and Archaeology (2009), pp. 111-140.

- B. Cunliffe, Europe Between the Oceans (2008), pp. 213-221.

- K.E. Barber et al., Late Holocene climatic history of northern Germany and Denmark: peat macrofossil investigations at Dosenmoor, Schleswig-Holstein, and Svanemose, Jutland, Boreas, vol. 33, no. 2 (2004), pp. 132-144.

- G.E. Hannon et al., The Bronze Age landscape of the Bjäre peninsula, southern Sweden, and its relationship to burial mounds, Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 35, no. 3 (March 2008), pp. 623-632.

- A. Kaliff, Gothic Connections: Contacts between eastern Scandinavia and the southern Baltic coast 1000 BC – 500 AD, Occasional Papers in Archaeology 26, (Uppsala 2001).

- A. Aikio, On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory, Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuren Aikakauskirja/Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne, vol. 91 (2006), pp. 9-55

- Noel D. Broadbent, The search for a past: the prehistory of the indigenous Saami in northern coastal Sweden, in Vesa-Pekka Herva (ed.), People, Material Culture and Environment in the North: Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Archaeological Conference, University of Oulu, 18-23 August 2004 (2006), pp. 13-25.

- K. Tambets et al,The western and eastern roots of the Saami: The story of genetic outliers toldby mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes, American Journal of HumanGenetics, vol. 74, no. 4 (2004), pp. 661-682. The haplotype found among 9 out of 10 Saami I1 men (14 at DYS 19, 23 at DYS 390, 10 at DYS 391, 11 at DYS 392, 13 at DYS 393) seems closest to that common in haplogroup I1d, found predomimantly in Norway and Finland.See http://www.familytreedna.com/public/yDNA_I1/

- S. Perdikaris, Pre-Roman Iron Age Scandinavia, in P. Bogucki and P.J. Crabtree (eds.), Ancient Europe 8000 BC–AD 1000: Encyclopaedia of the Barbarian World, Vol. I The Mesolithic to Copper Age (c. 8000-2000 B.C.) (2004).

- J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997), pp. 321-2.

- Tacitus, Germania, chap.1.

- D. A. Ringe, A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006), p. 213.

- S. Perdikaris, Pre-Roman Iron Age Scandinavia, in P. Bogucki and P.J. Crabtree (eds.), Ancient Europe 8000 BC–AD 1000: Encyclopaedia of the Barbarian World, Vol. I The Mesolithic to Copper Age (c. 8000-2000 B.C.) (2004).

- V. Blažek, On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey, Linguistica online (November 2005); J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams (eds.), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997), p. 22; O.W. Robinson, Old English and its closest relatives: a survey of the earliest Germanic languages (1994), p. 16 gives an earlier date (c. 150 AD) for the earliest runes.

- B. Fagan, The Little Ice Age: How climate made history 1300-1850 (2000), chapter 1.

- A. Woolf, Apartheid and Economics in Anglo-Saxon England, chapter 10 in N. Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (2007); P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), chap. 6: Franks and Anglo-Saxons.

- P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), p. 306.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History, 17. 8.3.

- P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), p. 306.

- The distribution of certain Germanic place-names suggests that some of the movement into Britain came from Saxony via the Low Countries and the Pas de Calais, with settlers opting to cross to Britain rather than press further westward into Neustria. See J. Udolph, Namenkundliche Studien zum Germanenproblem, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Ergänzungsbände 9 (1994); S. Hilsberg, Place-Names and Settlement History: Aspects of Selected Topographical Elements on the Continent and in England, MA thesis, Leipzig 2009: online http://place-names.co.uk/ .

- H. Hamerow, Early Medieval Settlements: The archaeology of rural communities in North-West Europe 400-900 (2002), chapter 2.

- J. Montgomery et al., Continuity or Colonization in Anglo-Saxon England? Isotope Evidence for Mobility, Subsistence Practice, and Status at West Heslerton, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 126 (2005), pp. 123–138.

- Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, chapters 23-25.

- Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, I.15.

- H. Hamerow, Early Medieval Settlements (2002), pp. 108-10.

- A. Woolf, Apartheid and Economics in Anglo-Saxon England, chapter 10 in N. Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (2007); P. Heather, Empires and Barbarians (2009), chap. 6: Franks and Anglo-Saxons, maps 11-12.

- M.E. Weale, Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 19 (2002), pp. 1008-1021; C. Capelli et al., A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles, Current Biology, vol. 13 (May 27, 2003), pp. 979–984; S.Goodacre et al., Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods, Heredity, vol. 95 (2005), pp. 129–135.

- B. Winney et al., People of the British Isles: preliminary analysis of genotypes and surnames in a UK-control population, European Journal of Human Genetics advance online publication, 10 August 2011.

- Ramos-Luis et al., Phylogeography of French male lineages, Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series, vol. 2 (2009), pp. 439–441; unpublished data from this study supplied by its authors.

- S. Rootsi et al., Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 75 (2004), pp.128-137.

- C. Capelli et al., A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles, Current Biology, vol. 13 (May 27, 2003), pp. 979–984.

- A. Moffat and J. Wilson, The Scots: A Genetic Journey (2011).

0 Comentarios